In November 2015, the BBC and RTE jointly carried out a poll and programme on a united Ireland. The poll, carried out by Behavioural and Attitudes, asked a thousand people in Northern Ireland and a thousand in the Republic about the constitutional question and other issues. [The main findings were posted by Mick Fealty at Slugger O’Toole ; full Report here].

Such polls are carried out every year or so. Previous include the BBC in 2013 and Belfast Telegraph in 2014. As well as being interesting to those interested in the subject, they serve a practical use. Under the Good Friday Agreement, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland may hold a border poll if:

“at any time it appears likely to him that a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be part of the United Kingdom and form part of a united Ireland”.

The BBC/RTE poll suggests that a border poll – let alone a united Ireland – is unlikely in the near future. In Northern Ireland, re-unification in the short to medium term received minority support, not only in the province as a whole but also among Catholics (unfortunately religion remains a very good indicator for political stance in Northern Ireland, as the results below demonstrate). The status-quo – devolution – was most preferred. Though a sizable minority opted for direct rule from London.

| [Northern Ireland] In the short to medium term, do you think Northern Ireland should … | ||||

| Catholic | Protestant | Other/None | Total NI | |

| Direct Rule | 14% | 30% | 32% | 24% |

| Devolution | 38% | 49% | 27% | 42% |

| United Ireland | 27% | 3% | 6% | 13% |

| Other | 3% | 0% | 6% | 3% |

| Don’t Know | 18% | 15% | 29% | 18% |

| Behavioural & Attitudes (page 638) | ||||

Excluding Don’t Knows, Direct Rule had 30% support, Devolution 51%, United Ireland 16%, and Other 3-4%. Thus Northern Ireland remaining as part of the United Kingdom in the short to medium term was supported by at least 81%. Again, only a minority of Northern Catholics and a tiny minority of Protestants chose a united Ireland.

Predictably, the Republic of Ireland was more enthusiastic about a 32-country state. Excluding Don’t Knows was as follows: Direct Rule 11%, Devolution 44% and United Ireland 45%. A larger majority south of the border said they would like to see re-unification in their lifetime.

| [Northern Ireland] Would you like to see a united Ireland in your lifetime? | ||||

| Catholic | Protestant | Other/None | Total NI | |

| Yes | 57% | 12% | 18% | 30% |

| No | 14% | 68% | 37% | 43% |

| Don’t Know | 29% | 20% | 44% | 27% |

| Behavioural & Attitudes (page 643) | ||||

Nationalists/republicans were largely disappointed and unionists content with the Northern Irish results. And like previous polls (see below) some commentators, politicians and members of the public set out to discredit the poll on social media. However nationalists may be happier with results from the question “Would you like to see a united Ireland in your lifetime”. Excluding Don’t Knows (which at 27% was large for this question): Yes 41% and No 59%. Reunification evidently remains an aspiration for most Northern Catholics, even if a sizable minority said No or Don’t Know.

Protestants are more decisively against a united Ireland than Catholics are in favour of it. Yet the 12% of Protestants who would like to see it is noteworthy. It’s possible that some meant a united Ireland under British rule, but this is unlikely. A 2014 Belfast Telegraph – Lucid Talk poll similarly found that 10% of Protestants would like to see “unity in 20 years”. So a few Protestants appear to be open to the possibility.

Regarding Catholics, the above findings may seem innocuous. For decades most Catholics voted for the SDLP who advocated power-sharing. Now that this goal has been achieved, despite its ongoing fragility, most in that community are fairly content. At the same time a united Ireland remains an aspiration for most.

This intuitive narrative has been contradicted, however, by the the most regular poll on public opinion in Northern Ireland: the Life and Times Survey.

Source: Life and Times Survey (NIRELND)

Source: Life and Times Survey (NIRELND)

As can be seen above, when asked about “long-term policy for Northern Ireland”, a united Ireland has minority support from Catholics and minuscule support from Protestants. In fact in 2014 barely a third of Catholics wanted a united Ireland in the long term. So in terms of aspirations, the BBC/RTE poll said something different. Which may provide some solace to committed nationalists and republicans.

Previous Polls

As mentioned by Susan McKay on the live programme and Diarmuid Ferriter in an Irish Times article, the BBC/RTE poll is nothing new. Citing John Whyte’s Interpreting Northern Ireland, Ferriter notes that:

“…Whyte identified 25 polls between 1973 and 1989 about the North’s constitutional status, and there were broad consistencies. A united Ireland had minuscule support from Protestants, far from complete support from Catholics, and the solution that attracted most support from both communities was power-sharing”.

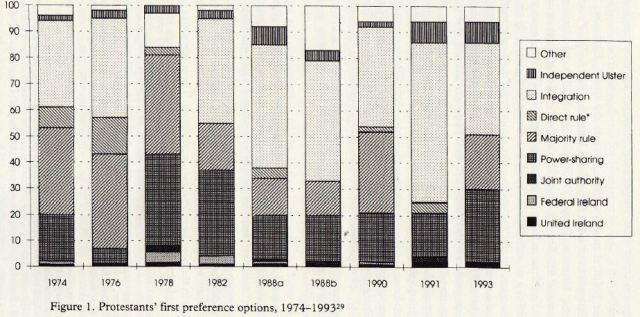

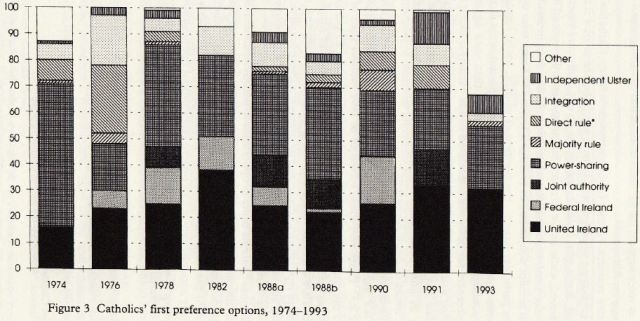

A selection of these polls were reproduced in Jennifer Todd and Joseph Ruane’s The dynamics of conflict in Northern Ireland:

There were differences, often because of events or trends. Power-sharing gets majority support from Catholics in 1974, the year of Sunningdale Agreement. Support for a federal Ireland among Catholics and majority rule among Protestants also come and go. (A big drawback from the two bar-charts is that the same questions were not asked in each poll).

Still, there are clear “broad consistencies” between polls since 1968 and the BBC/RTE poll half a century later. Quoting John Whyte who was writing in 1990 (page 82 of Interpreting Northern Ireland):

“The option which attracts most widespread support in both communities is power-sharing. Among Catholics, it has normally been the most first preference, with percentages selecting it usually in the thirties or forties. If asked whether it is acceptable, percentages rise much higher – to 88 in April 1974, 83 in January 1978, 75 in May 1982, 78 in January 1986, 78 again in February 1989. Among Protestants, positive support has been considerably lower – normally in the tens or twenties. But the percentage finding it acceptable has been larger – 52, 51, 45, 61, and 57 in the five polls just cited”

Power sharing had long been the most supported option for Catholics. Protestants, who probably narrowly voted in favour of the Good Friday Agreement, were less sure. Again citing Whyte (page 80), there tended to be “widespread support” among Catholics for a united Ireland as a long-term objective. While Protestants showed little support, apart from stray polls, like in 1982 when 15% said they could accept a federal united Ireland. So despite the Troubles, the Peace Process, and large shifts in support for parties, public opinion on the fundamental constitutional and political questions has remained remarkably similar during the past 50 years.

Despite regular comment that these polls are faulty, the fact that similar findings have been repeated so often makes complaints silly. For a majority of Northern Irish Catholics, a united Ireland has always been a long-term goal. The problem for Nationalists is that the long-term in the 1960/70/80s is now. Reunification is an aspiration, but its fulfillment keeps being pushed into the distance. Protestants are more coherent in their opposition to a united Ireland than Catholics are in their support. It’s for these reasons that the Union appears to be safe.

More to reunification than economics?

The only new question in the BBC/RTE survey was on whether tax would be higher, lower or the same in a united Ireland. Arguably this is a superficial question. Particularly for those who desire a 32 county socialist (or at least left-leaning) republic where everyone would “pay more tax” for greater state involvement in the economy and society. But the question is probably a good proxy for how support changes when the economic success or failure of reunification is considered. After all, lower taxes, whether income tax or water charges, is the mainstay for all the main political parties, North and South.

Higher taxes is hardly an unrealistic scenario if partition was ended anytime soon. The billions London transfers to Belfast each year would have to be matched. And there would certainly be other costs, such amalgamating public services and extra security to deal with any Loyalist unrest. Something akin to the post-1990 German Solidaritätszuschlag (Solidarity Tax) would be required. The old solution from nationalists/republicans that it would all be paid for by UK reparations and/or EU and US aid is unrealistic. At least at the levels that would be required to run a newly reunified state. In any case, as shown in the tables below, the question has significant results.

| [Republic of Ireland] And would you be in favour or again a united Ireland if it meant.. | |||

| In favour of a UI | Against a UI | Don’t Know | |

| Pay less tax | 73% | 8% | 18% |

| No change | 63% | 14% | 24% |

| Pay more tax | 31% | 44% | 25% |

| Behavioural & Attitudes (page 411) | |||

The change in support and opposition is starkest in the Republic. Excluding Don’t Knows, opposition was only 9% when “Pay less tax”, rising to 18% when “No change”, and to a majority of 59% when “Pay more tax”. Southern support for irredentism is clearly qualified by how much money one will gain or lose. Self-interest trumps nationalism.

| [Northern Ireland] And would you be in favour or against a united Ireland if it meant… | |||

| In favour of a UI | Against a UI | Don’t Know | |

| Pay less tax | 32% | 39% | 27% |

| No change | 22% | 45% | 30% |

| Pay more tax | 11% | 56% | 30% |

| Behavioural & Attitudes (page 644) | |||

Support for a United Ireland also falls in Northern Ireland when it’s proposed taxes will be higher. But the answers for “Pay less tax” are perhaps more revealing. Breakdown by religion is below.

| [Northern Ireland] “And would you be in favour or against a united Ireland if it meant you would have to pay less tax. | ||||

| Catholic | Protestant | Other/None | Total NI | |

| In favour | 57% | 15% | 21% | 32% |

| Against | 11% | 63% | 33% | 39% |

| Don’t Know | 30% | 19% | 44% | 29% |

| Behavioural & Attitudes (page 649) | ||||

Like their southern brethren, Northern Catholics enthusiasm declines for a united Ireland when more tax is required. But it’s worth comparing the above table on “And would you be in favour or against a united Ireland if it meant you would have to pay less tax” with the second table in this post “Would you like to see a united Ireland in your lifetime”. (The reason the former question does not add up to 100% is because 2% “refused” to answer the tax question, for some reason).

The two questions broken down by religion reveal very similar results. Catholics support for a united Ireland is about the same when the question is about lifetime aspiration and when it’s proposed that they would pay less tax. And Protestant opposition is about the same for both questions. So even when it is proposed that reunification would make people better off, opinions do not change. A possible conclusion, therefore, is that Catholics/Nationalists’ opinion on re-unification is elastic when tax is taken into account, whereas Protestants/Unionists stance is inelastic. In other words, Unionists are still opposed to a United Ireland even when it’s possible they would be more prosperous.

This result (admittedly in only one poll) is not good for a strain of nationalist thought that has been dominant in the southern establishment. The idea being that if the Republic prospered, northern Unionists would be more inclined to support (or at least acquiesce in) the reunification of Ireland. The thesis’ voice grew in the 1950/60s and is associated with the likes of Sean Lemass, T.K. Whitaker and Garret Fitzgerald. Southern advocacy for reunification has become dormant because of the peace process and financial crisis, though a more up-to-date articulation has been by Slugger O’Toole’s David McCann.

Arguing for a united Ireland on an economic basis makes sense for obvious reasons. Jobs and taxes dominate political debate. But it’s also a response to the long held Unionist economic arguments against Dublin rule. An argument has of course turned 180 degrees. Long gone is Henry Cooke’s boast during Ulster’s early industrialisation: “look at Belfast and be a Repeler if you can”. No longer is it that Ulster cannot afford to be a country with the backward south, but that Ulster would be too great a burden on the Republic.

Sources: Maddison Project; Birnie & Hitchens; 1913 is all-Ireland and 2009 is GVA per capita

As can be seen in the graph above, Ireland’s GDP per capita (adjusted for purchasing power) surpassed Northern Ireland’s in the mid-1990s. Yet the fact that Unionist opposition, whether in public or in polls, did not alter significantly during the Celtic Tiger suggests that their opposition to Dublin rule is more inherent. As the economic facts changed, their arguments against a united Ireland seamlessly moved from the south being a basket-case to the North being a basket-case that the south could not afford. And while Unionists’ arguments for the Union has changed, their fundamental position has not. Nor are they alone in deeply held convictions. In the 1950s when Ireland was experiencing economic hardship and mass emigration to the UK, and the North was enjoying the benefits of the new welfare state, there was few calls by nationalists to consider re-joining the Union. There is more to life than economics.

A simple response to the naysayers and polling by those who would vote Yes in a border poll is that once a campaign is under way opinion will change. Because no plebiscite has been called there has been little debate and discussion about what a united Ireland would look like. Indeed, the last serious economic study on reunification was carried out by DKM Consultants for the New Ireland Forum in 1984. With the prospect of Brexit and Scottish independence, some nationalists and republicans hope that a break-up of the UK would lead to a serious reconsideration of the Union by the Protestant community.

This may be so. But needing a political crisis to achieve support means that you have failed to convince in more peaceful times. There are no guarantee that a state formed in such circumstances will prosper, economically and otherwise. And while it’s true that there has been little debate about the ins and outs of reunification, that is partly the fault of nationalists and republicans for not making arguments. Sinn Fein’s “debate” on it essentially started and ended when Alex Maskey could not answer the basic question of what would happen to the NHS in a united Ireland. For the time being unionists should be reassured by the BBC/RTE poll.